HIV criminalisation describes the unjust application of criminal law to people living with HIV based solely on their HIV status. This includes the use of HIV-specific criminal statutes or general criminal laws to prosecute people living with HIV for unintentional HIV transmission, perceived or potential HIV exposure, and/or non-disclosure of known HIV-positive status. HIV criminalisation is a global phenomenon that undermines both human rights and public health, thereby weakening the HIV response.

What behaviours are targeted by these laws?

HIV criminalisation takes place either using HIV-specific criminal statutes, or by applying general criminal laws exclusively or disproportionately against people with HIV.

In many instances, HIV criminalisation laws are exceedingly broad – either in their explicit wording, or in the way they have been interpreted and applied – making people living with HIV (and those perceived by authorities to be at risk of HIV) extremely vulnerable to a wide range of human rights violations.

Usually these laws are used to prosecute individuals aware they are living with HIV who allegedly did not disclose their HIV status prior to sexual relations (HIV non-disclosure); are perceived to have potentially exposed others to HIV (HIV exposure); or thought to have transmitted HIV (HIV transmission).

In many countries a person living with HIV who is found guilty of other ‘crimes’ – notably, but not exclusively, sex work, as well someone who spits at or bites law enforcement personnel during their arrest or whilst incarcerated – often faces enhanced sentencing even when HIV exposure or transmission was not possible or was – at most – a very small risk.

How widespread is HIV criminalisation?

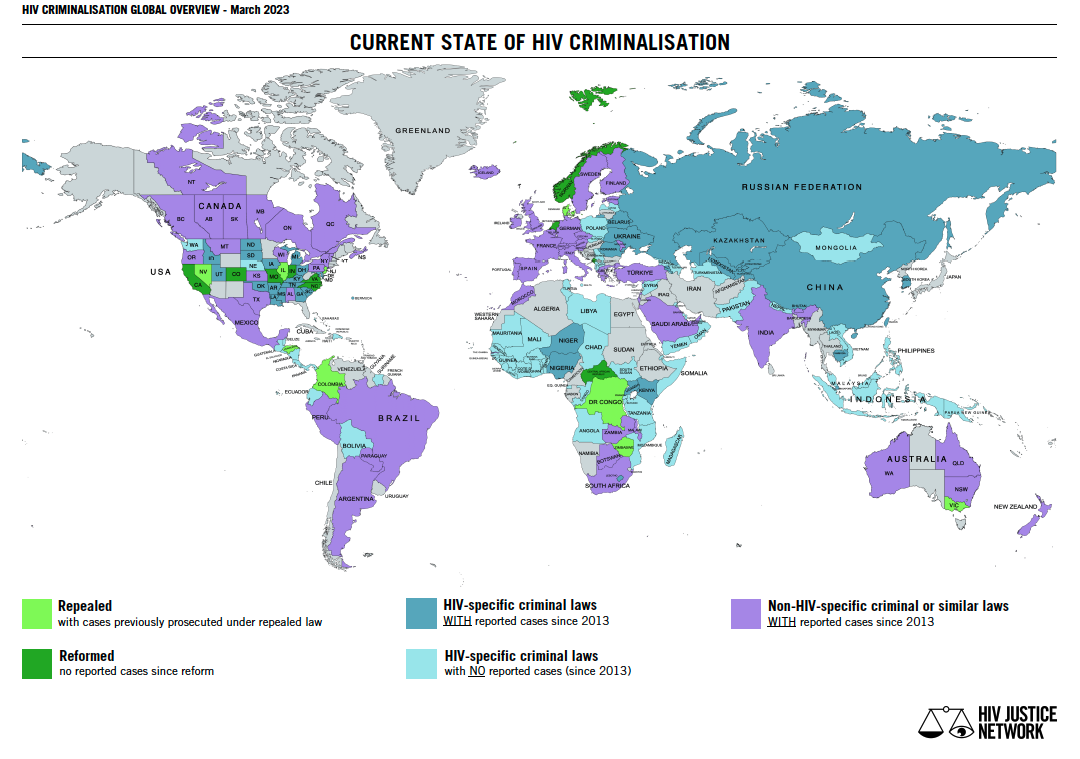

As of March 2023, 91 countries (114 jurisdictions) have some form of HIV-specific criminal law, and another 41 countries (61 jurisdictions) are known to have applied general criminal laws to prosecute people living with HIV for alleged HIV non-disclosure, perceived or potential HIV exposure, and/or non-intentional transmission.

To download a pdf of the global overview map, with further details on repealed and reformed laws, click here.

To see the latest cases, and detailed information on each country, visit HJN’s Global HIV Criminalisation Database.

How does HIV criminalisation affect the HIV response?

HIV criminalisation undermines public health objectives in many ways.

Prosecutions, and the media they attract, single out and sensationalise HIV in a way that is highly stigmatising, framing HIV diagnosis as a catastrophe and people with HIV as an inherent threat to society. Suggesting criminal charges are a primary or appropriate response to any perceived or potential HIV exposure is inappropriate. Such stigma makes HIV disclosure to intimate partners even more difficult. Evidence suggests this could deter people from getting tested, particularly those from communities highly vulnerable to HIV infection. Encouraging HIV testing is an essential part of an effective response: an HIV-positive diagnosis is the first step to accessing health-enhancing antiretroviral treatment, and an HIV-negative result the first step to accessing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), both of which are key HIV prevention tools.

HIV criminalisation can also undermine the therapeutic relationship between people living with HIV and healthcare professionals, reducing their capacity to provide support, including providing frank advice about risk reduction strategies. In fact, healthcare providers have been forced to testify in court about communications with their patients, evidence which is used to pursue convictions against their patients.

HIV criminalisation is also affecting research into HIV prevention, treatment and care, because of concerns that otherwise confidential data may be legally obtained by law enforcement in the context of a criminal case. It is also compounding concerns about the use of new technologies to track the epidemic, such as molecular HIV surveillance.

How does HIV criminalisation impact human rights?

HIV criminalisation undermines the human rights of people living with HIV, many of whom are also members of marginalised or additionally criminalised communities. Threatening to go to police with accusations of HIV non-disclosure has been used as a form of abuse or retaliation against current and former HIV-positive partners. HIV criminalisation places people living with HIV—particularly but not only women—at heightened risk of violence and abuse and ignores the reality that some may not be able to safely disclose their status or in a position to ask their partner to use a condom.

Stigmatising statements from law enforcement or public health agencies, and media coverage, including full names and photographs—even of those merely subject to allegations—can result in public disclosure of a person’s HIV status and accusations of serious criminal conduct, leading to loss of employment and housing, social ostracism or even physical violence. Investigations and prosecutions often have a disproportionate impact on racial and sexual minorities, migrants, and women. Poorly-resourced accused may be without access to adequate legal representation.

In certain cases, some of the most serious offences in a country’s criminal law (e.g., aggravated assault, sexual assault and attempted murder) have been used to prosecute alleged non-disclosure in the context of consensual sexual encounters. Penalties are often vastly disproportionate to any harm caused, including lengthy jail terms and/or designation as a sex offender. People without citizenship in their country of residence may also be deported upon conviction, which can result in loss of medical care.

How does HIV criminalisation intersect with other forms of criminalisation, discrimination and stigma?

Far from being a legitimate tool for public health, HIV criminalisation is more often used as a proxy mechanism for increased state control, policing of marginalised groups and punishment of social vulnerability.

HIV criminalisation is also often used with, and compounds the harms caused by, other criminal or punitive legal sanctions such as those used against sex workers, trans people, irregular migrants, people who use drugs, and where same sex sexual relationships are criminalised.

The likelihood of prosecution under HIV criminalisation laws is increased for those who experience intersecting discrimination, including on the basis of race, ethnicity, migrant status, sex, gender identity or sexual orientation, as well as people in prison and other closed settings, unsheltered individuals, and people with disabilities, notably with mental health issues.

Where can I find further information?

UNAIDS’ Global AIDS Strategy (2021-2026) explicitly recognises HIV criminalisation as a barrier to ending HIV as a public health threat by 2030, and has set bold new global targets, specifically that fewer than 10% of countries criminalise overly-broad HIV non-disclosure, exposure or transmission by 2025, and fewer than 10% of people living with HIV experience stigma and discrimination in a wide range of settings, including the criminal legal system.

You can find much more information on the HIV Justice Network website and by visiting the HIV Justice Academy. The following key global level documents provide essential background that informs our work.

-

UNAIDS/UNDP Policy Brief, 2008

UNAIDS/UNDP Policy Brief, 2008

-

'Oslo Declaration on HIV Criminalisation', 2012

'Oslo Declaration on HIV Criminalisation', 2012

-

UNAIDS, 'Ending overly broad criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission: Critical scientific, medical and legal considerations', 2013

UNAIDS, 'Ending overly broad criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission: Critical scientific, medical and legal considerations', 2013

-

Barré‐Sinoussi et al. 'Expert consensus statement on the science of HIV in the context of criminal law', 2018

Barré‐Sinoussi et al. 'Expert consensus statement on the science of HIV in the context of criminal law', 2018

-

UNDP, 'Guidance for prosecutors on HIV-related Criminal Cases', 2021

UNDP, 'Guidance for prosecutors on HIV-related Criminal Cases', 2021